If you scroll through the list of the 255 official highway historical markers maintained by the state of New Hampshire, you will find 21 bridges, two memorials to the 45th parallel, several references to Daniel Webster and a few oddities, like the sign labeled “Bungtown.”

What you won’t find is much geekiness.

Amid all those markers scattered along state roads, there’s distressingly little celebration of New Hampshire’s technical and scientific accomplishments.

But we’re going to fix that, you and I. And we’re going to start with something basic – or, rather, BASIC.

In the coming months we are going to get the New Hampshire Historical Highway Marker system to add a marker letting the world know that BASIC, the first user-friendly computer language, and the Dartmouth Time-Sharing System, an important precursor to the internet, were both born in Hanover in 1964. Because they matter at least as much as a covered bridge.

Automatic transmission for software

I talked to Drysdale after I decided on that these joint computer accomplishments at Dartmouth would be my first candidate for adding some geeky goodness to our historical markers.

BASIC and the time-sharing system known as DTSS were created in tandem by two Dartmouth mathematicians who wanted to make the exciting new world of computing more usable: John Kemeny, who later was president of the college and is probably the most famous geek in New Hampshire history, and Thomas Kurtz.

They certainly succeeded. Search through any history of computing and you’ll find celebration of BASIC, which among other things helped Bill Gates launch Microsoft, and mention of the role that DTSS played in developing time-sharing and networking.

Or you can ask baby boomers like me, most of whom were taught BASIC in high school. We’ll bore you senseless reminiscing about our clever programs like 20 PRINT “Help, I’m trapped in a dot-matrix printer!”

If we went to college in the Northeast, we’ll also talk about DTSS because it was our gateway into the world of big-time computing. I remember signing into it at my college computer lab before wasting time with a lunar lander simulation. (I always crashed.)

So Kemeny and Kurtz’s creation is perfect for a state historical marker, which brings us to how to get that done.

The process for creating a marker is pretty simple: Write up your suggested idea, give supporting evidence, get at least 20 state residents to sign the petition (that’s where you will come in, dear reader), then submit it to Department of Historical Resources and wait.

I started by approaching Dartmouth College, which already has at least one plaque on campus honoring BASIC and DTSS and which created a big website when BASIC turned 50 (dartmouth.edu/basicfifty/basic.html) in 2014 as well as a DTSS website that includes an emulator (dtss.dartmouth.edu). They gave my idea an unofficial thumbs-up and sent me to Drysdale, who came to Dartmouth in 1978 to teach computer science and who just retired in June.

Drysdale told me that although he arrived more than a decade after 1964, when BASIC and DTSS were born, they still loomed large.

“DTSS was still the basic way that people got computing on campus. It was not until ’84 we started bringing in personal computers, which moved people off of the time-sharing system,” he said. “And BASIC was a very important and real thing. We still taught the introductory class in S-Basic, a version of BASIC … Everybody who took a math course at Dartmouth listened to several taped lectures by Kemeny and wrote four little programs, one to approximate the area of a circle.”

I suggested the metaphor of BASIC as training wheels for writing programs, but Drysdale didn’t think it was quite right. “Not training wheels. Maybe closer to automatic transmission, because most people didn’t have to move beyond BASIC for what they wanted to do.”

Then he made a suggestion that should have been obvious: I should contact Kurtz, who is still very much with us. (Kemeny died in 1992.)

Computing for the ‘masses’

Thomas Kurtz lives in Hanover and is known to many locals for his organizational prowess, not to mention game-playing prowess, in bridge tournaments. When I approached him with my idea, he happily responded to some questions by email.

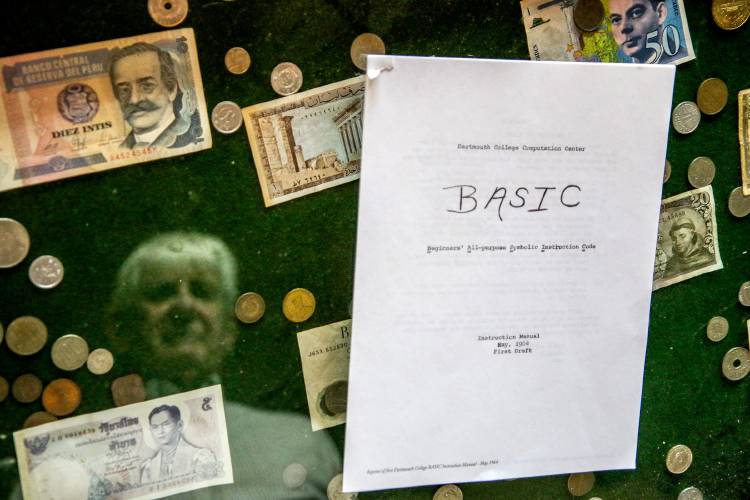

Kurtz said that creating BASIC (Beginner’s All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code) and a system by which many people could remotely use a computer at the same time went hand in hand, both driven by the idea of helping the masses use computers.

“Of course, by ‘masses’ we meant ‘Dartmouth students’; in particular those not majoring in the sciences. (The graduates who in later years became CEOs, etc., normally majored in the Social Sciences or Humanities.) It turned out that we also meant high school students,” Kurtz wrote, parentheses included.

“By 1963-64 we both had had about 10-15 years’ experience with computing and with the ‘crude’ programming languages available in those early days. Another point: Around 1959 we (i.e., Dartmouth) obtained its first real computer, a Royal McBee (later General Precision) LGP-30. Its use by students convinced us to require all students in the second-term math course to write several simple (5- or 10-line) computer programs in a simple language that we called SCALP, which was a subset of the Algol programming language around at that time.

“By 1963 we convinced ourselves and the management of Dartmouth that we needed a bigger machine. And, as it turned out, the concept of time-sharing as a more efficient way to access a computer (in terms of people-time, if not in computer-time) was just coming into being at MIT and Carnegie-Mellon.”

“Kemeny wrote the first BASIC compiler (yes, it was a compiler, not an interpreter!). A team of brilliant Dartmouth undergraduate students wrote the DTSS time-sharing operating system. I was the director of the computer center.”

The result was Dartmouth Time-Sharing System, which allowed multiple people to use the same computer from different locations at once. It and BASIC were rolled out in 1964 and marked a real change in computing – and also put Dartmouth on the global map for the new and exciting world of software and computers.

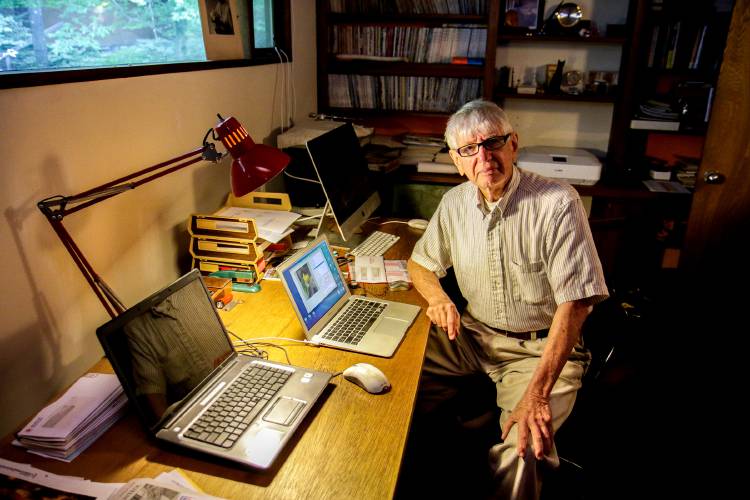

Tom Kurtz sits in his computer room in his home in Hanover, N.H., on Thursday, Aug. 9, 2018 (Valley News – August Frank) Copyright Valley News. May not be reprinted or used online without permission. Send requests to permission@vnews.com.

What’s next?

So it’s clear that BASIC and DTSS deserve a historical marker. Now all that’s needed is to write the text and figure out where to put it.

The sign can have one or two lines of title and up to 630 characters – almost three tweets’ worth. Putting together enough information to inform the newbie without exasperating the knowledgeable won’t be easy, but between Kurtz and Drysdale, who know what they’re talking about, and me, who knows how to edit text to fit, we can do it.

As for a location, the final decision will be up to the Department of Transportation, but we have to suggest a site.

The only other thing we need is public support in the form of a petition signed by at least 20 New Hampshire residents. I’m confident that more than enough Granite Geek readers will step forward. Watch this space, and/or sign up for the weekly Granite Geek newsletter at granitegeek.org, and I’ll let you know when the time comes.

In the meantime, we need to start thinking about what our next target for a geeky state historical marker should be. Should we honor the first home video game created in Nashua? The twin-primes conjecture breakthrough at UNH? Dean Kamen’s infusion pump for diabetics? Better yet, something cool I’ve never heard of?

Send me your thoughts and we’ll get things rolling. Just make sure it doesn’t have anything to do with a covered bridge – 21 of those signs is enough.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor

We know the Kurtz family and would like to help in any way we can. This is a great – and long overdue- idea.

The term “artificial intelligence” was coined for a workshop held at Dartmouth in 1956. Given its prominence today, perhaps the fact that the field was born in New Hampshire would be worth a marker?

As part of the team that exported BASIC to the world it will be a constant reminder of the genius of Kurtz and Kemeny, Many thanks.

Chuck Morrissey, founder of Time Share Corporation