Last week my wife and I hiked up the back side of the Mt. Sunapee range – I’m waiting until there’s real snow in the Whites to drive that far – and were surprised to find a fancy cairn on the ridge, shown above. It was a couple miles south of the ski area, maybe a half-mile south of Lake Solitude (which is really just a big pond, but very pretty) on the 50-mile Monadnock-Sunapee Greenway trail.

I assumed it was a marker for a T-intersection but there was no side trail. Puzzled, I wrote the Monadnock Sunapee Greenway Trail Club, Their response:

That cairn has been recently rebuilt to its present condition. We don’t know by who, but the original purpose is as an USGS benchmark. It’s gotten more attention this year so we”re thinking on putting up a sign that reads – “This very point of New Hampshire was first established in 1872 and monumented/benchmarked and described in 1873. It was part of the Unites States Coast & Geodetic Survey program to accurately map the United States. Think about it, over 140 years ago, surveyors stood here with a transit turning angles to triangulate between benchmarks, to measure and map the hills and valleys you see before you. Please respect and do not disturb history.”

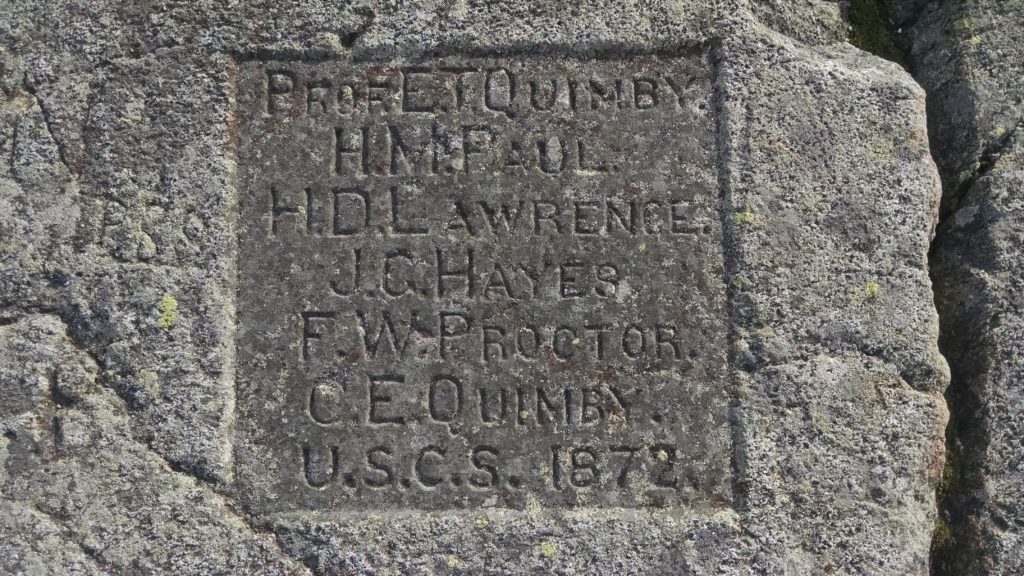

Hey, I replied, I know all about that! I wrote a story two years ago about this survey, the first serious effort to map New Hampshire. I learned about it after seeing this plaque carved into the stone atop Mount Kearsarge:

You can read my whole 2018 story right here including my visit to the state archives to see the notebooks made by Prof. E. T. Quimby of Dartmouth and his survey team. Here’s a bit of the story to whet your appetite, including this laborious effort to make mountaintops visible to each other:

“Select a pole (from which it is better to remove the bark) six to eight inches in diameter at the butt, and 12 or 15 feet in length. … Fasten to the top of the pole a nail keg, 10 to 15 inches in diameter” that is covered with black cambric. Make sure to mark “the pole below the keg with alternate bands of white and black.”

Take this contraption to the top of your selected point and set it upright, Hitchcock wrote, adding: “Too great care cannot be taken to place the pole exactly vertical and to secure it from being moved by winds, cattle, or any other cause.” A black keg atop a striped pole was relatively easy to see from 10 or 20 or 50 or miles away.

Quimby’s notes say that in October 1869 his team used this system to make measurements on six mountains, including Kearsarge, “although the weather was very unfavorable,” using a 10-inch theodolite from Thayer School of Engineering at Dartmouth. By 1874, he had done a dozen locations and eventually he covered twice as many.

These mountaintop measurements were the important framework for the resulting triangulation maps, but not the whole thing. Quimby’s notebooks are filled with angle measurements from each of these mountains to specific places inside the big triangles.

And I do mean specific, including “the ridgepole of big barn” at Shaker Village in Canterbury and the “gold ball atop dome” of the State House. I even found an 1871 notebook that lists the angle measurement from Crotched Mountain to a barn that still stands in my town.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor

Yes! I worked with USC&GS back in the seventies. Still turning angles with the theodolite.

Much work at night with lighted signals and angles to various stars.

Daytime sightings included finials, water towers, gargoles. Several times down a Coast Guard helicopter cable in Alaska to set up a sighting pole over a monument.

Romantic, but GPS sure takes the cake now.

I have lived here all my life and I have just learned much, thank you!