On my roof are some solar panels. They’re good for me but the question is, are they good for the power grid?

Some people say no, that they destabilize the system providing electricity throughout New England by ruining the finances of “baseline” plants and leaving us hanging at night. Some people say yes, that they improve the grid by adding resiliency, providing a source of electricity distinct from vulnerable power plants, power lines or pipelines.

This debate is old hat to Amro Farid, Ph.D., a professor of engineering at Dartmouth College who has long studied energy systems.

“It’s clear the American electric power system needs to evolve for a bunch of different reasons,” Farid said. But it’s not clear how it should evolve.

“The conventional wisdom … leads to contentious discussions: ‘We need to invest in resiliency of the grid’ or ‘We need to invest in the sustainability of the grid’,” Farid said. In other words, should we concentrate on strengthening the power grid against massive storms and cyberattacks, or concentrate on making it able to power civilization without further destroying the global ecosystem?

The argument is endless because both sides are desirable and common sense can’t choose between them. As an academic engineer, Farid wondered if there was an objective, quantitative way to settle the dispute.

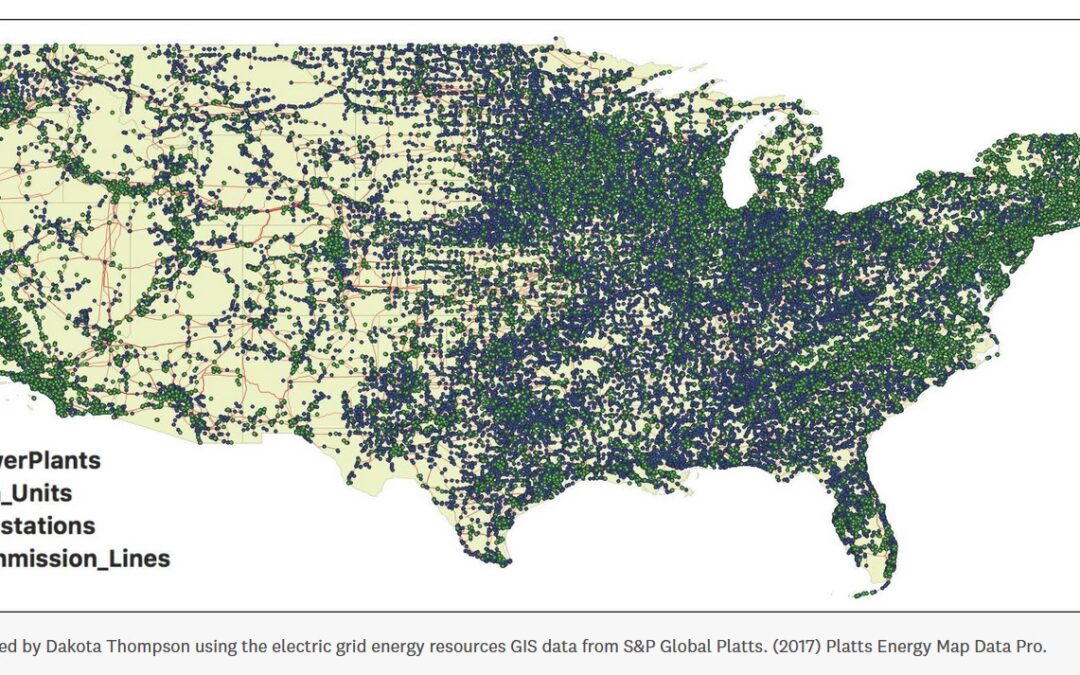

Enter hetero-functional graph theory, which Farid and his doctoral students at Dartmouth have used to test any trade-offs via a computer model of the nation’s staggeringly complex electrical system.

Farid developed hetero-functional graph theory to analyze networks of networks. As he explained it, network theory deals with nodes, which are single-function objects like a house or a substation and the edges that connect them, like power lines. That’s fine for the old, one-way power grid but on today’s grid a node can have several functions. My home, for example, is a power consumer on a cloudy day, a power producer on a sunny day, and it could be a power-storage site if I had batteries (alas, too expensive).

In ways that I can’t explain– “We’ll leave the math to my grad students,” he assured me – hetero-functional graph theory can handle nodes with multiple roles and still analyze the network.

A side note before we get to the results. A comment I often hear is “you can prove anything you want with computer models” – in other words, that they’re useless in making real-world decisions.

That is a silly thing to say, as shown by the fact that every industry uses computer models all the time to make decisions about investment and planning and procedures. They are a bedrock of the modern economy.

A useful computer model is open to examination and testing, as compared to the secret algorithms used by Facebook or Google to shape our online life. Being open makes it a tool that researchers and industrialists alike can use.

“You can always revise a model – revise it and see the impacts,” Farid said. “That’s the value of it.”

Now back to our column topic!

With their model, Farid and students added three elements that are key to decarbonizing the grid, then ran the mathematics to see what effect these had on the grid’s ability to bounce back from random problems like huge storms, and from deliberate targeted problems like ransomware attacks.

The three elements they added were: more distributed energy sources like my rooftop solar panels; more energy storage like the big batteries that New Hampshire Electric Cooperative turned on last week; and turning the radial, tree-like power grid into a “mesh grid,” a web-like structure with two-way flows of energy.

The results, he says, show that these decarbonization techniques make the grid more resilient; they don’t weaken it.

In other words, there’s actually no debate. The paper was published in IEEE Xplore with co-authors Dakota Thompson, a Ph.D. student, and postdoc Wester Schoonenberg.

The basic reason that sustainability increases reliability, Farid said, is that the new technologies provide more options if things go wrong. In a properly designed system, my solar panels could keep me going and maybe also a neighbor or two if nearby power lines fail. A mesh network could route electricity forward or backward around problems. Storage could keep an “island” of power running while everything else is fixed.

“There is no structural trade-off between grid sustainability and resilience enhancement,” he said. “None.”

Now come the caveats. (You knew there’d be a “yes, but …” section, didn’t you?)

This analysis looked at the static makeup of the grid but not the dynamic actions that are taken with that system. But technology alone is not a magic bullet, Farid said.

“The message is that just because we add solar, mesh grids and batteries to the system doesn’t mean we’re done, that all of a sudden we’re going to get resilience. We still need to make improvements in how the system works,” Farid said, ticking off some actions that are needed, like new control systems, better automation and the very hard job of changing how markets work.

“Making those investments is a positive step forward. But after that, you have to take the steps to ensure that you improve the way the system is operated,” he said.

In other words the tech is necessary for making the grid both resilient and sustainable but it’s not sufficient. To accomplish what we need to accomplish we will have to change our thinking, as well. Easier said than done.

And as long as we’re talking about harder tasks, Farid noted that this study encompasses only the electric system, which is about a third of our total energy usage.

“The next topic in our research project (with National Science Foundation) is to look at sustainability and resilience of the American multi-modal energy system,” he said. Not just electricity but all the other fuels, too: coal, natural gas, oil.

I mentioned that this sounds like a much harder problem and Farid agreed. “We’re going to have to beef up our computers.”

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor