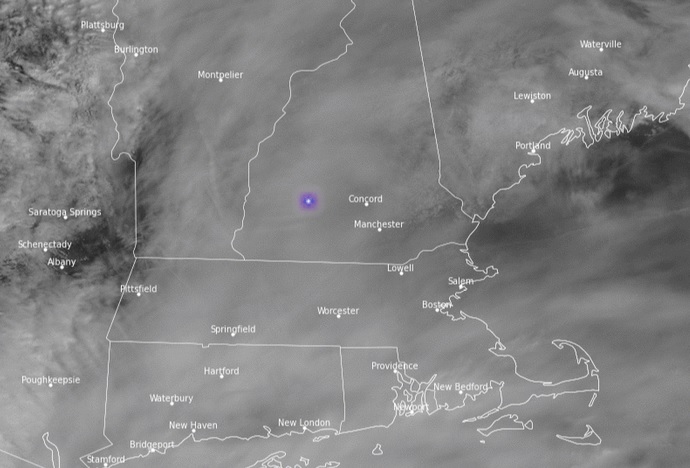

That boom which rattled southern N.H. and surrounding areas late Sunday morning now seems very likely to have been a meteor exploding, probably just a few tens of miles up. You may have seen the above picture from the GOES-16 satellite Geostationary Lightning Mapper, which shows a flash where no storms were causing any lightning at around 11:30 a.m. Sunday. Pretty conclusive.

(Something I learned from all these stories: a flash from an exploding meteoroid, which is the official term for rock in space before it burns up, is called a “bolide.” Now you know.)

One question I had is why most meteoroids burn up rather than explode. Part of the issue, I found after online exploration (“I did my research!” sounds much less impressive than it used to) is that meteoroids come from different sources: often they result from collisions of rocky asteroids, sometimes they’re bits of icy debris shed by comets, very occasionally they’re a piece of the moon or other planet knocked off by a meteor and captured by our gravity field. So they’re made of different material and enter the atmosphere at various speeds and angles, meaning they respond differently to the heat of re-entry.

It turns out that researchers at Purdue University and elsewhere looked into what makes them explode rather than burn up. (Here’s the university press release, with links to the research). Here’s the tl;dr summary:

When a meteor comes hurtling toward Earth, the high-pressure air in front of it seeps into its pores and cracks, pushing the body of the meteor apart and causing it to explode.

.

“There’s a big gradient between high-pressure air in front of the meteor and the vacuum of air behind it,” said Jay Melosh, a professor of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences at Purdue University and co-author of the paper. “If the air can move through the passages in the meteorite, it can easily get inside and blow off pieces.”

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor