Fans of Concord’s gasholder builder want to save the historic structure because of how it looks above the ground, but there’s an underground reason to keep it intact, as well.

That issue came up in a recent webinar for environmental firms held by the New Hampshire Business and Industry Association concerning hazardous waste and contaminated sites.

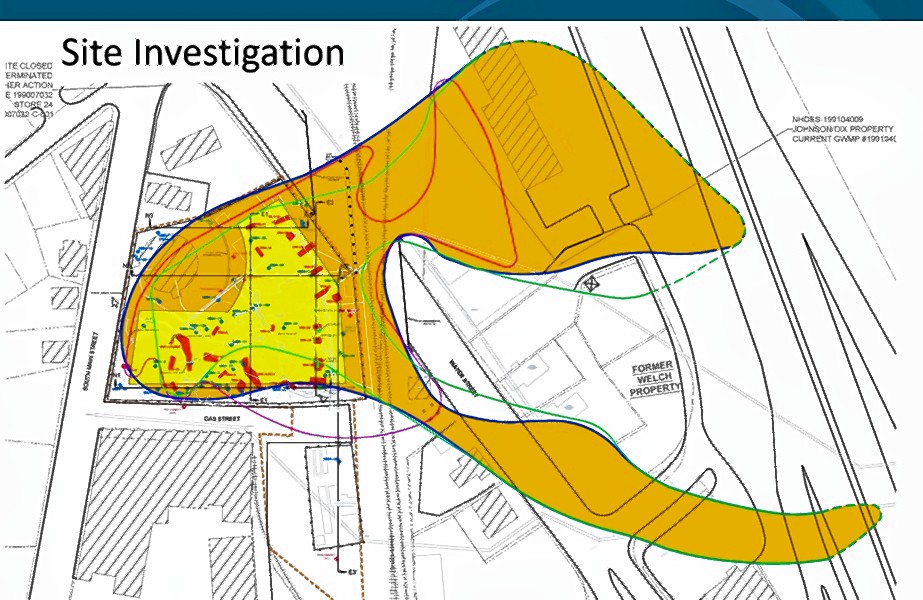

In one talk James Wieck of GZA GeoEnvironmental discussed ongoing efforts to preserve the 1888 gasholder, including monitoring subsurface pollution that was left behind by a century of processing coal to create a flammable gas, which was used for building heat in Concord before natural gas pipelines arrived in 1952.

The round brick building that held this gas has been empty for years and is in danger of falling apart. Efforts to save it have been organized by the community and emergency work to stabilize the structure are going on. Its long-term future remains uncertain.

The main pollution problem goes by the inelegant acronym DNAPL. This stands for dense nonaqueous phase liquids, in this case tar-like byproducts of coal processing that seeped into the ground during decades of storage and handling, threatening groundwater.

Most of the toxins were dug up and removed from the 2.4-acre site decades ago. But material had already oozed underground beyond the property boundaries, mostly to the east and south toward the Merrimack River, although it does not appear to be spreading any longer.

“It’s like an old can of paint that has splattered and has run out as far as the thickness of paint will allow,” Wieck told the webinar.

A series of monitoring wells have been dug to keep track of the spread and two wells are removing material that is found, he said. “It’s under 10 gallons over the course of a year – not much.” The monitoring will continue until the New Hampshire groundwater quality standards are met, and tar will be recovered as long as it is present in the wells where it is being recovered.

As for the gasholder building itself, however, there’s more uncertainty.

The building held manufactured coal gas under a floating cap that is 88 feet in diameter and weighs many tons. The gas was pumped in from the manufacturing building and held there, trapped between the cap and water, until it was used by downtown buildings for heat. The cap rose and sank depending on how much gas was stored at the time. Its weight provided pressure that sent the gas through pipelines to customers.

The gasholder’s historic importance comes from the fact that the cap and associated machinery is still intact. Many other gasholder buildings exist around the country, including a small one at St. Paul’s School, but this appears unique in still having all its machinery.

In 1994, some 700,000 gallons of water and sludge left over from this process was pumped out of the area under the cap. What’s unknown is whether any pollutants from that mix penetrated the soil beneath the building.

As long as the gasholder is in place and nothing shows up in monitoring wells, that’s not an issue. It’s another question if the gasholder building gets torn down because money can’t be found to save it.

“It acts as a physical barrier. … If that holder house is removed there will be a need to excavate more in that area that we couldn’t get access to,” Wieck said.

Liberty Utilities took ownership of the property in 2012 when it bought National Grid’s gas business. The company had threatened to tear it down but in April it signed a memorandum of understanding saying it would match donations up to about $500,000 to stabilize the building. Previous studies estimated that stabilizing the building, which is almost 30 feet high, would cost around $400,000, while preserving it as a long-term monument would cost at least a million dollars.

Turning it into a usable building would cost far more, especially with the uncertainty about subsoil pollution.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor

Slight correction: the image caption should say “I-93 runs north-south on the righthand edge of the map.”

D’oh!

(fixed)