Technology won’t succeed unless we’re ready for it. New Hampshire, where the population is getting older and we don’t have enough caregivers, needs to get ready for robots.

“In Japan, it is not shocking to think you will spend the last 10 years of your life with a robot. In New Hampshire, in New England, it is shocking,” said Momotaz Begum, assistant professor of computer science at UNH.

It shouldn’t be.

While New Hampshire is not facing as sharp a “demographic cliff” as Japan, where nearly one-third of the population is already over the age of 65, we are one of America’s oldest states and have a low birth rate. We face an increasing need for people to help care for those who are less able to care for themselves. Yet the lack of cheap housing makes it hard for people to live here while filling those poor-paying positions.

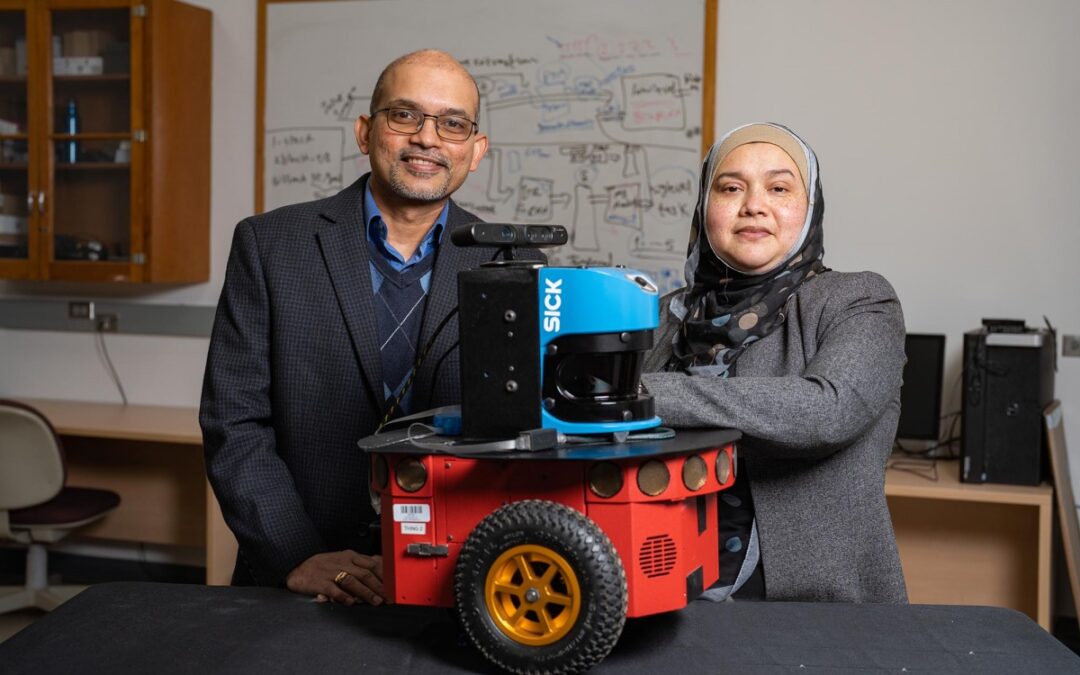

Begum and Sajay Arthanat, professor of occupational therapy at UNH, have received a $2.8 million grant from the National Institutes for Health to help bridge this gap in one area: caring for people with dementia in their own homes.

“We are not trying to replace some family member or caregiver. Obviously there is emotional attachment,” said Arthanat. “We’re not trying to replace that at all. This is a complimentary device, a tool to fill a gap or minimize a burden that caregivers give on a daily basis.”

A number of specific technical tools exist to help caregivers, from health alerts to anthropomorphic companions. This five-year project is seeking to use existing knowledge and technology to develop a single product that can monitor a person’s health and safety in their own home as well as provide some needs, from companionship to medication support, without another person having to be there.

You can see a video explanation of the project online.

“In general, robotics technology is not ready for unmonitored home deployment in an unstructured environment. When you put in another constraint – you will be helping people who have cognitive deficits – that makes it more tricky. We are not there yet,” said Begum. “It involves solving a lot of challenges: software, sensing, understanding what is happening in an unstructured environment … These are all general AI problems. ”

Begum said the biggest technical constraint involves sensing apparatus. There are plenty of things like motion sensors on doors to make sure a patient doesn’t wander, and sensors on dispensers to ensure medication is taken property, “but they can capture only so much information.”

What you really need are cameras, but processing that much information to make real-time decisions is “computationally challenging,” as she puts it, and runs into the very complex questions about patient privacy. How much automated monitoring is legal and ethical when dealing with a person who may not be able to understand the implications?

Security is also a big concern, since it seems to be almost impossible to keep hackers out of any network. “We have a cybersecurity expert in our team. We are being proactive about it,” said Arthanat.

As is the case with any technology that gets used by untrained people, difficult questions have to be answered about what techies call UX for “user experience” and form factor, which normal folks call “what it looks like.”

Begum said one of the big questions is how much a care robot needs to look human-ish.

“There will be some level of anthropomorphism,” she said, but it’s unclear how useful that might be. While there isn’t a ton of data yet there is some evidence that looking more technical, more robotic rather than humanoid, might make it easier for people to understand and follow directions.

For the time being, the prototypes will be robotic due to real-world constraints. “We have to balance appearance, robustness and cost,” she said. “We do not have a platform that is affordable and at the same time robust and has an anthropomorphism that people might want to see.”

The rough schedule calls for scaling up and developing protocols in the next year and a half, using everybody from professors to post-grads to graduate and possibly undergraduate students, then deploying in the homes of perhaps a half-dozen subjects. Testing will take place partly in the home simulation lab that is part of the Occupational Therapy program, an example of the benefit of bringing together researchers from departments that don’t often work together.

The reality, however, is that even after five years we’re not going to be able to buy a Wildcat-branded dementia carebot. The situation they’re tackling is just too complex, too difficult. But that’s part of what research universities are for: to try for advances in places where the marketplace’s invisible hand doesn’t see enough profit.

“We’re looking at a decade from now before this might become a proven solution,” said Arthanat. “You have to start now so the next generation of caregivers can reap the benefits of this.”

Speaking as somebody just entering the promised (or perhaps dreaded) land of the potentially retired, this isn’t a moment too soon.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor