If we have no choice but to go through an ecological catastrophe, we might as well try to learn something from it.

This is the idea behind a unique experiment in the Hubbard Brook Forest that will protect about 300 ash trees from the ravages of the emerald ash borer to help us understand how the fast-moving destruction of an entire species will change our forests.

“In 5 years, 10 years, these experimental plots will be the only grove of mature ash trees, white ash, that are left in the forest in North America,” said Matt Ayres, a biology professor at Dartmouth College who is one of the lead investigators on the ash protection experiment. “We are not trying to stop it – nothing can be done to save our ash trees. We’re trying to learn about the consequences.”

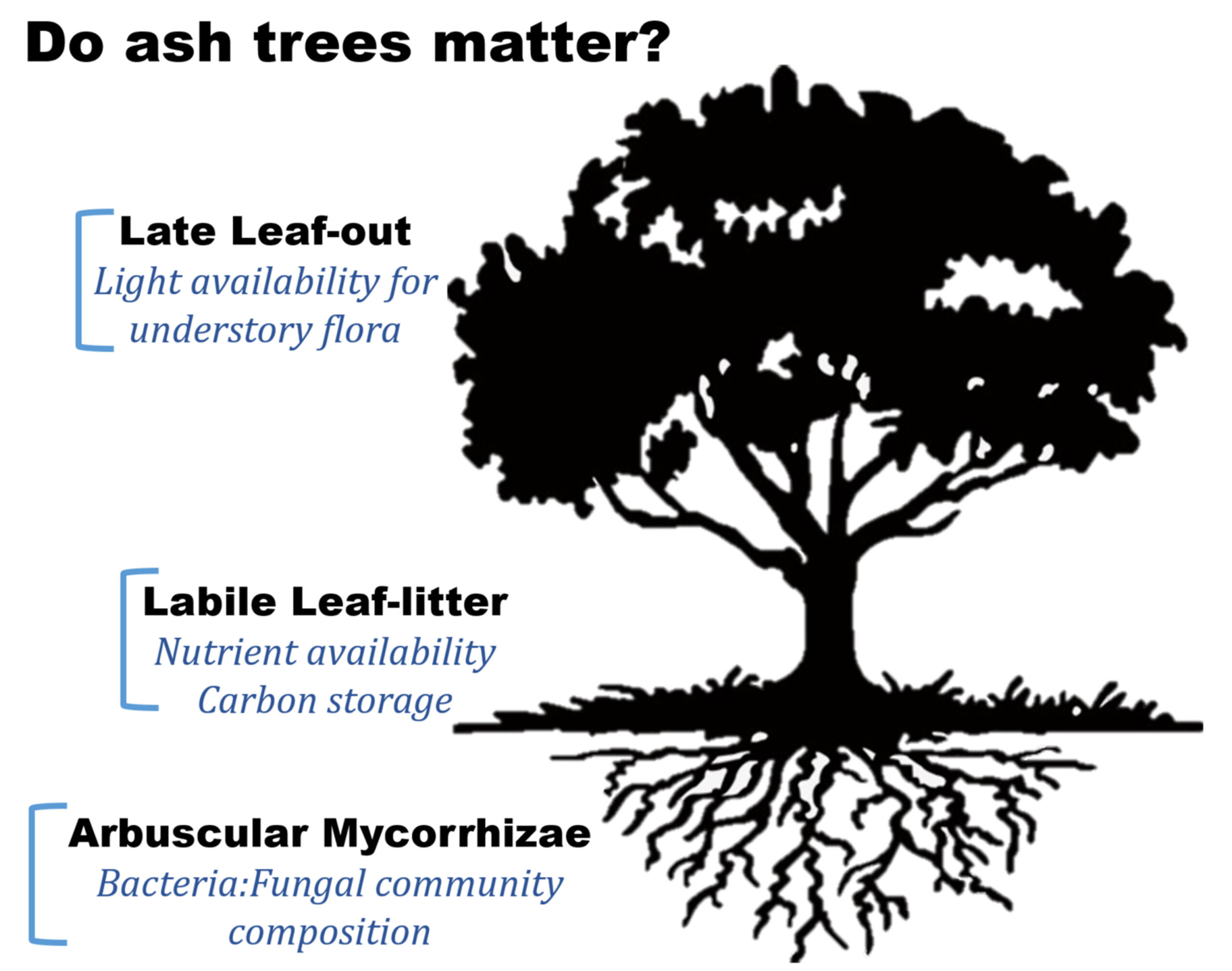

Among the issues to be studied, Ayres said, are the effect on forest soils of losing all our ash trees.

Ash leaves decompose much more quickly than the leaves of other deciduous trees in the valley, so soils around them have a different mix of nutrients that affects everything from insects to plants to fungi.

“One of the questions we’re particularly interested in is how do trees affect soil? We all know that soil affects plants, know more or less that plants can also affect the soil but we don’t know the scale, the magnitude, the details,” Ayres said.

Another topic of interest comes from the fact that ash trees leaf out slightly later in the spring than other trees, allowing the sun to reach the ground for a longer period.

“Those habitats are a haven for spring ephemerals – trillium, trout lilly, several dozen other beautiful plants whose biology is adapted to taking advantage of one month or so in the spring of sufficient light reaching the forest floor,” Ayres said. “For those plants having even another week of that is huge.”

Ash trees’ demise will hurt those plants. This project will help quantify how bad it is and how much effect the decline of spring ephemerals will have on the ecosystem.

You probably know the story of emerald ash borer or EAB. It was accidentally introduced into the US within the past decade, probably via packing material or pallets for imported goods (the route of many invasive insects). Its larvae feed under the bark along the trunk and larger branches of ash trees, draining nutrients and killing the tree within a year or two of first infection. It is proving 100% fatal.

EAB has been spreading steadily since it was detected in Michigan in 2002 and has been found in about half of New Hampshire. Since it has no natural enemies and likes our climate, before long it will exist throughout the entire state including all of Hubbard Brook’s 8,700 acres. It was first found in this forest last year.

The ash protection experiment was designed and organized within a year after EAB came knocking on Hubbard Brook’s door. That’s very fast by the standards of big (well, big-ish) science.

Involving researchers at Dartmouth and UNH as well as folks from the White Mountain National Forest and U.S. Forest Service, it doesn’t even have dedicated funding although work has already begun.

“For the time being we’ve figured out how to make this happen,” Ayres said of the funding question. “People are writing grant proposals.”

The experiment design is fairly straightforward. They’ve chosen about 300 mature ash trees, mostly white ash, in 64 plots throughout the Hubbard Brook valley and are injecting a random selection with emamectin benzoate, a pesticide that targets the nervous system of the EAB. As long as the injections continue, roughly every four years, the trees will be protected.

“It’s the reverse of a typical large-scale Hubbard Brook experiment,” Ayres said in a press release. “Most of our large-scale manipulations involve the removal of trees. EAB is creating that for us already — we are looking at what happens to the forest under trees which remain.”

This summer has seen a scramble to collect samples of soil and water around the plots to provide the all-important baseline data that can be used in future experiments.

The Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest was established in 1955 as one of 20 experimental forests and rangelands overseen by the federal government precisely to host this kind of long-term ecosystem research. The most famous work done here helped discover acid rain but it has been the laboratory for more research papers than you can count.

It’s sad that this latest project was triggered by yet another ecosystem-wide disaster, but that seems to be the world we’re living in.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor