A pilot program for curbside collection of hard-to-recycle items like power cords and coffee capsules has been launched in Vermont and may come to Concord someday, keeping them out of the trash and turning them back into useful material.

But while it is an admirable effort, its limit reflects how landfills are going to keep growing as long as we shove the cost of wasteful products onto taxpayers and individuals rather than manufacturers.

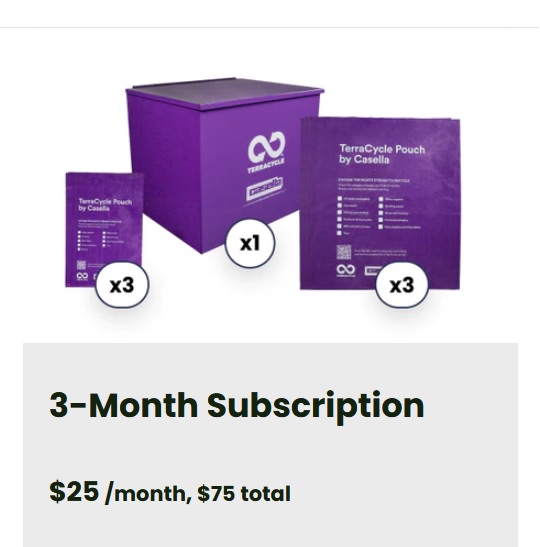

Under the pilot, called Terracycle Pouch, people in Burlington, Vermont, can sign up for a monthly pickup of pouches holding used coffee capsules, eyewear, office supplies, pet food packaging, toys, and various types of plastic packaging. The pouches are picked up once a month separately from regular curbside trash and taken to a facility for the difficult and expensive process of separating out the useful bits.

The program is a test by TerraCycle, a firm that has been recycling difficult products for two decades, and Casella, the waste-management company with the contract for Burlington as well as Concord and many other places. TerraCycle does a similar pickup on its own in a few places but this is the first time it has partnered with an existing trash firm to do it, which is its preferred model. Most of the material it recycles comes from public or corporate-sponsored collection sites.

If all goes well, TerraCycle Pouch could be expanded to other Casella markets like Concord, as well as cities where other waste-management firms operate.

“One of the problems we’re always looking to solve is contamination in a curbside recycling program,” said Jeff Weld of Casella Waste Systems. “These create problems with machinery, it doesn’t work one way or another. This is another way to get that hard-to-recycle material out of the waste stream.”

This program is an interesting way for TerraCycle to expand its innovative recycling work into homes. And goodness knows we need to keep stuff out of landfills. So why aren’t I more excited?

Because it costs homeowners $25 a month to participate, meaning it will never do more than nibble around the edges of the problem.

“This is like cable TV. … Today we view waste management as pretty basic – everybody bought the basic plan,” said Tom Szaky, CEO of TerraCycle. “This is like the idea of putting premium services on top of those basic ones.”

Szaky agrees that the cost is an obstacle and points to the economic reality of recycling, which for many modern products can’t be recouped by selling what you collect. “The material value will never justify the cost,” he said.

He gave the example of those coffee capsules used in K Cups and similar machines, which are tossed out by the millions every day in the U.S.

“If it costs $1 to get a certain amount of coffee capsules from you to us … let’s say it costs us another 50 cents to shred them, separate organics from aluminum,” he said. “The aluminum probably sells for 2 cents; coffee grounds are given away for free for composting. So that’s $1.48 to be recouped.”

In municipal recycling systems, these costs can be recouped directly by taxes or indirectly by avoiding landfill fees. That might work for profitable materials like aluminum cans or cardboard and for sometimes-profitable materials like waste paper, but not when the cost gets too high. Those items just get trashed and we get into big fights about how to keep expanding our landfills.

TerraCyclePouch is recouping the recycling cost through what is essentially individual donations from households volunteering to pay almost $1 a day to reduce their trash impact. That’s fine as far as it goes, but depending on do-gooders to take up a burden out of guilt will never solve a widespread problem.

The only way to really reduce waste is to put the cost on the manufacturer, giving them a strong incentive to innovate their way around the problem. If Coke had to pay to collect their empty plastic bottles you can bet they’d figure out a way to sell fizzy sugar water without plastic bottles. The invisible hand of the marketplace would make the world better.

But this method, called “producer pays,” would be painful. Costs of many things would rise, sometimes to the point that they wouldn’t be made anymore.

For example, it might be impossible to manufacture a coffee-grounds-holding thingy that can easily make a single cup of coffee and also won’t end up in landfills unless it costs 20 times the current price. This would limit the potential market so much that no company would bother doing it and K Cups would disappear. We’d have to go back to making entire pots of coffee!

On a less glib note, I’m sure lots of useful things built of several different types of plastic glued and joined together, items that are almost impossible to recycle, would also disappear from store shelves if this cost-shift happened. It would not be pretty.

But we’re already paying this cost indirectly, in taxes for waste management and in pollution. Forcing the cost onto manufacturers at least would make it obvious so we could try to respond rationally.

Yet you and I know it will never happen, at least not in the U.S. So we’ll have to celebrate small bits of hopeful change.

You can learn more about the program at terracyclepouch.com.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor

Just wanted to share that the companies have been selling reusable k-cups for at least 10 years. They work great.

You give examples of useful things, like k-cups (although for me the coffee doesn’t justify the plastic). I think the best example is crazy, useless packaging. Clear plastic shells, annoying plastic shelf hangers attached to clothes, food on plastic foam trays, stuff now in big plastic jugs that used to come powdered in a box…it is everywhere. Mostly just cheap marketing. Sometimes we can not buy the thing that has more plastic packaging than worth, it other times we actually need the thing in the plastic clamshell. Drives me nuts. I look down the aisles in the stores and think, every plastic container I see there is headed for the dump. This week and next week and on and on.