A citizen science project called Raspberry Shake is allowing a few in New Hampshire to tune into the “unheard symphony of the planet” – as well as things that aren’t quite so symphonic.

“I can tell when vehicles are driving by on the road. And it picked up a jogger running by once: a really heavy guy going downhill,” said Ric Werme of Sutton.

Werme, a retired software engineer, is one of a handful of people who have turned the small, do-it-yourself computer called Raspberry Pi into a seismograph, the device that detects vibrations and is used by scientists to tell us the size of earthquakes. He had it when he lived in Boscawen and now it sits in his Sutton garage, detecting everything from cars to small quakes to the explosion of a meteor overhead.

“The meteor explosion it picked up was largely an infrasound thing,” said Werme, referring to sound waves that are too low for humans to hear but which can carry energy. Infrasound is an area of interest to Werme and was the reason he got involved with Raspberry Shake in the first place.

“(A Raspberry Shake in) Antrim picked up the exact same signal, except earlier. We’re confident the meteor broke up in several short events close to each other, so each of the booms we heard came from meteor breaking, not sonic booms,” he said.

Raspberry Pi computers have long been a favorite of the digital arm of the do-it-yourself set, used to create everything from cheap gaming consoles to pirate radio stations to replacements for desktop PCs. Turning it into a seismograph involves a heavy magnet suspended in a coil. Movement makes one move but not the other, generating an electric signal that the device translates into data.

“It’s a little more complicated than setting up a router but not too bad,” said Werme.

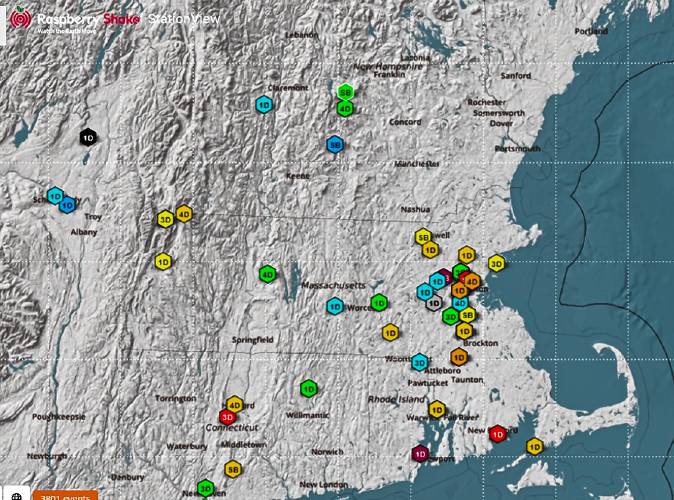

About 1,600 Raspberry Shakes exist around the planet, most of them live-streaming their open-access data to form a huge real-time seismic network. As of Monday three stations were reporting from New Hampshire, all clustered in the Sunapee region for some reason. Vermont and Maine each have one; Massachusetts has a couple of dozen, mostly in greater Boston.

To find out more, check raspberryshake.org/.

The global network is made up of a mixed bag, from hobbyists to teachers to scientific researchers. A New York Times story on it quoted people saying they detected everything from badgers digging in the yard to the HVAC system turning on in a nearby school. I stole that “unheard symphony of the planet” line from one enthusiast quoted by the Times.

“I live next door to the TDS telecom central office and I can tell you down to the second when their generator test starts every Monday morning,” Werme said.

If you have time on your hands, you might even use it as a sort of speed gun.

“There’s a crack in the road near my house. I will see two pulses from when the wheels (of a vehicle) hit it, then the background signal increases where the vehicle is passing my house. … It made me think it would be interesting to take the timing between two cracks and determine the speed of the vehicle. Maybe I could determine its size, too, from the magnitude of the signal,” he said.

Citizen-science networks, where lots of amateurs collect some type of data that is compiled online, have become a staple of modern research and monitoring. For example, I’ve been collecting precipitation data for more than a decade as part of one of them, with the awkward name Community Collaborative Rain, Hail, Snow Network (CoCoRaHS). More than 10,000 people are part of that every day and our measurements are used by the National Weather Service to fine-tune observations about storms and potential flooding.

So far as I know, the Raspberry Shake network isn’t part of any research or formal observation of seismic data but it seems like it could be a way to fine-tune our understanding of geology.

If nothing else, I could see the data being used in court cases about disruption or damage caused by construction. It’s also useful to help answer one of the most frequent queries in social media.

“When I lived in Boscawen, I made a name for myself with it,” said Werme. “A common question on Facebook was “Was that an earthquake?” and I got the reputation of being the first person to answer.”

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor