We’ve all gotten familiar with the idea of a hub-and-spoke system for everything from airline flights (you have to visit Newark before you can visit L.A.) to home computer networks (except for the printer, which can never seen to get connected).

But I wasn’t expecting to see it in satellites.

Yet hub-and-spoke is the reason that NASA has chosen UNH to lead a new solar-wind-studying project with the cool name of Helioswarm.

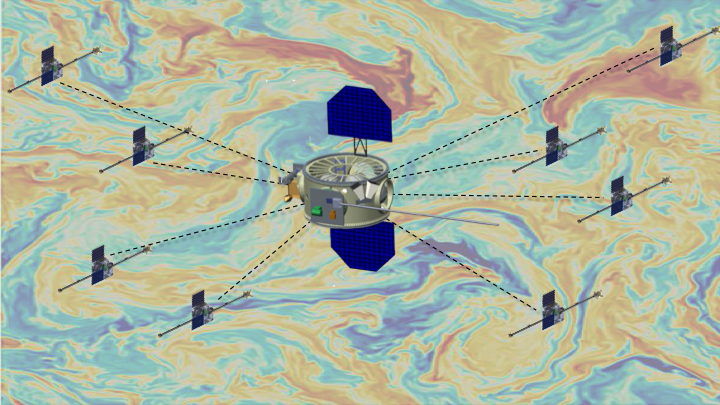

NASA announced last week that UNH, through its Earth, Oceans and Space institute, has won a $250 million contest to lead the design and implementation of the project to study the solar wind. It will launch in 2028 (space science is not for the impatient) and will feature a mid-sized satellite, the hub, orbiting Earth while eight small satellites, called nodes, orbit the hub at the end of invisible spokes.

The whole shebang is designed to analyze the barrage of charged particles that come off the sun. The goal is not so much to predict whether another solar storm is going to kill 40 satellites, as happened to the latest SpaceX launch, but to get a deeper understanding how turbulence acts in solar wind, which will help give a deeper understanding of a lot of what happens in and around all stars.

“We are discovering in astrophysics the importance of turbulence … Right now they have to make assumptions about it. We’re going to make measurements that will eliminate the assumptions,” said Harlan Spence, a professor of physics and astronomy who is HelioSwarm’s principal investigator, the research-science equivalent of CEO.

Turbulence is a staggeringly complicated topic, described by Richard Feynman as the last unsolved problem of classical physics. This difficulty in predicting how wind and water act over time is a big reason why weather forecasts aren’t more precise, and it’s no easier with solar wind.

“On the one hand it’s intuitive what’s going on – when you’re in an airplane you feel the bumps – but understanding how it actually works, especially in space, is just really complicated,” said Spence.

That’s great, but why are they doing it with such a complicated dance of satellites? That’s the key to Helioswarm.

The individual components of the swarm are relatively straightforward. Spence said the nodes basically act like an airport windsock, gathering density speed and direction of the solar wind, while the hub also has an Ion Electrostatic Analyzer that is “a fancy thermometer, if you want to think of it that way.”

What’s different is the way they all act together. The maneuverable nodes, which have their own propulsion, will take intricate trips around the hub as it goes through a type of orbit known as lunar resonant orbit, sometimes close to Earth and sometimes as far away as the moon. This will allow Helioswarm to draw a picture of what’s happening in a way that no single measuring site ever could.

“Imagine having a single weather station in the middle of the U.S. trying to predict the weather based on that one station,” said Spence. “There are a number of scientific questions posed virtually since the beginning of (space science) that we can’t answer because we’re only flying one or two or our spacecraft in the same region at the same time. We can’t get multipoint, simultaenous measurements.”

A key part of the design is the hub-and-spoke model. The nodes will communicate only with the hub, which will then send the data down to Earth.

This means the node satellites can be much smaller and simpler than if each was communicating with earth, and makes operation of the network easier and cheaper, too. “If you imagine operating nine spacecraft the old-fashioned way, there’s a lot of human intervention.”

Helioswarm will be taking advantage of work that NASA Ames Research Center has been doing in a project called Starling. “It’s named after the bird – those birds swarm, they sort of act collectively. That’s the idea here,” said Spence.

The current plan is for the entire package to launch at once, and the eight none satellites to break off and go their own separate ways once out in space, although details may change.

The HelioSwarm mission will involve some two dozen 25 UNH faculty, researchers, scientists and students as well as managers, engineers and technical staff. The team will work directly with NASA Ames Research Center in California. Helioswarm is the latest sizable space award for EOS, which has become one of the university’s big selling points.

Helioswarm is slated to last just one year after launch, which will “carry the swarm through all of the different regions we need,” Spence said.

But it may well last beyond that because space missions have a habit of outliving their initial life span. There’s a reason for that, Spence said: “The environment is fairly benign. The challenge is getting into space … but once launched and successful, missions can last a long time.”

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor