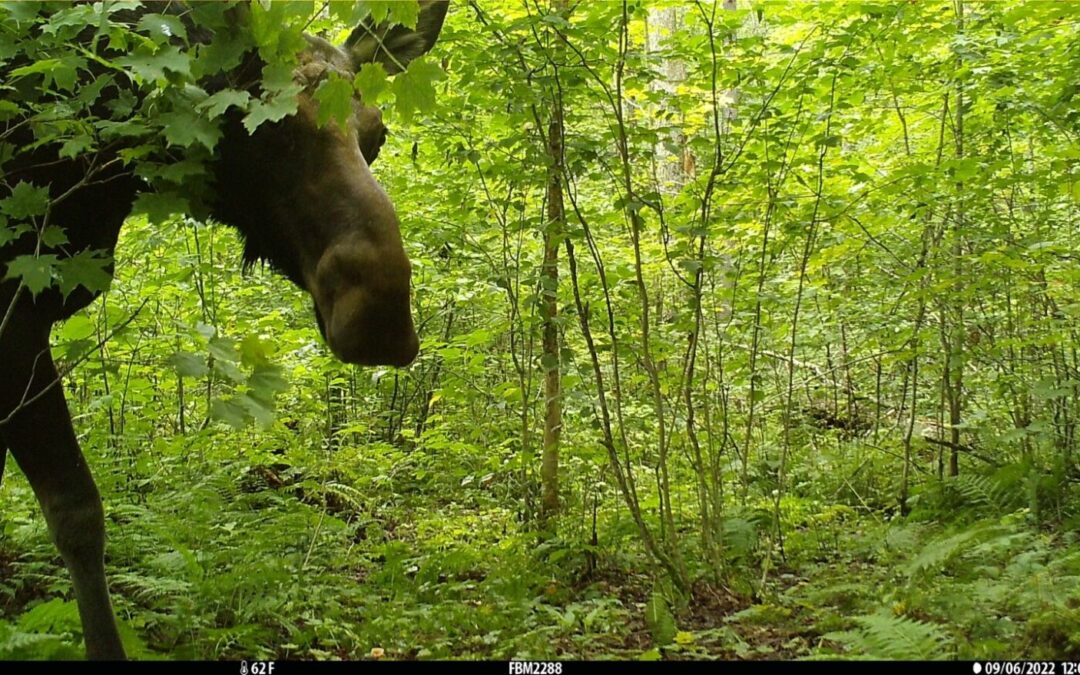

From UNH News Service: Even though they are a major draw for tourists, and important for forest habitat, moose are shy and can be a challenge to track to help protect from adversities like certain forest and land management and environmental factors like the increase of winter ticks. Researchers at the University of New Hampshire have turned to publicly available online videos to help develop a method to assess wild moose sounds, in their natural environment, and identify the distinct differences by age and sex in an important first step in creating an acoustic network that could help track, monitor and protect moose populations.

“By tracking moose, scientists can predict how forest habitat affects moose distribution,” said Laura Kloepper, an assistant professor of biological sciences at UNH and a scientist at the New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station. “Specifically, how habitat disturbances, like those caused by some timber management, affect where moose prefer to live and how those preferences change with the seasons or the time of day. Since moose have a wide roaming range and low population densities, monitoring them is an ever-present challenge that could be aided by non-invasive technologies like a moose acoustic sensor.”

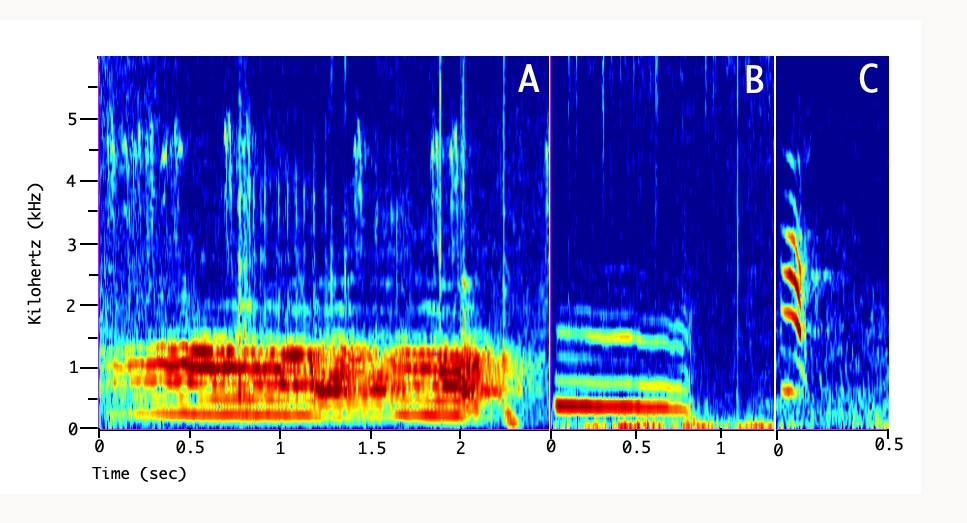

Visual representation of audience frequencies or vocalizations, known as representative spectrograms, from a) cow, b) bull, and c) calf. Credit: UNH

In their study, published in the journal JASA Express Letters, researchers outline first steps to creating a moose acoustic network by using publicly available videos to first identify the species by sex and age. The online videos, crowdsourced from hunters and recreationalists, allowed them to better identify and separate the vocal characteristics of male and female moose and calves. From the videos, they adapted the bioacoustic data—sounds produced by or affecting the moose—to identify differences in moose calls and characterize them by age and sex.

After viewing close to 20 videos, they had collected 673 calls—199 from cows (females), 255 from bulls (males) and 219 from calves. The calls were distinct and had quantifiable vocalization differences in peak frequency, center frequency, bandwidth and duration across the groups of cow, bull and calf moose. Although individual variations existed, there were clear differences between age and sex classes, with the most pronounced differences between bulls and calves. In general, bull moose had the lowest-frequency calls, cows had mid-range frequency calls and calves had the highest-frequency calls.

“Because moose can be highly elusive, we relied on an underutilized resource for animal behavior—videos captured by the public,” said Kloepper. ”The acoustic results are an important first step in obtaining audio from direct observations of a hard-to-capture and understudied species that will allow us to now help in identifying moose.”

Researchers say the data obtained from the public videos will also help them to scan and identify the vocalizations from other long-term video and acoustic recordings across the N.H. forests. Future work will include networks of calibrated acoustic recorders across a landscape to develop an automated detector and determine moose population density and occupancy to inform forest management.

This work was supported by the N.H. Agricultural Experiment Station through joint funding from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture and the state of New Hampshire. It conducted in partnership with NH Fish and Game Department

Co-authors include Alex Zager, Sonja Ahlberg, Olivia Boyan, Jocelyn Brierly, Valerie Eddington and Remington Moll, all at UNH.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor