Timing, they say, is everything, and the timing of a push for broadband internet within New Hampshire Electric Cooperative couldn’t be much better.

“The argument is a whole lot easier now than it was a year ago,” said Dick Knox, one of a number of people behind a petition drive at the state’s only electricity cooperative.

A proposal added to the annual board of directors’ balloting, the first such drive in the cooperatives’ 81-year history, would change the cooperative’s articles of incorporation to add “facilitating access to broadband internet for members” as a core purpose.

In other words, it says that as long you’re sending electricity over wires to our home, why not send fast internet over fiber-optic cables – because if there’s one thing the past two months have shown it’s that we all need broadband.

If it passes this would be a first for an electric cooperative in the Northeast, but not nationally. More than 210 electric cooperates have gotten into the broadband business in other parts of the country, particularly the Upper Midwest, according to a group called Institute for Local Self-Reliance. Cooperatives, which are owned by the customers, are strong in the Plains, where they have stuck around after bringing electricity and telephone services to farm areas a century ago when utilities wouldn’t do it.

The New Hampshire Electric Cooperative’s board opposed the petition by a 7-3 even though they support the goal because they’re afraid it will cost too much and “divert resources from the co-op’s existing core focus on delivering safe, reliable, affordable electric service to its members.” In a statement, the board said the coop hired a consultant to examine the issue in 2018 and concluded that the downside was too great.

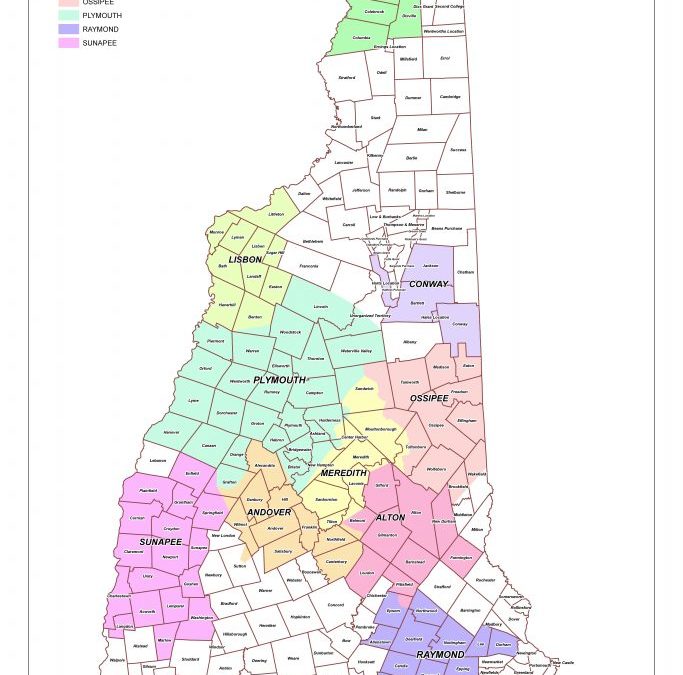

NHEC, headquartered in Plymouth, has about 84,000 customers in 115 communities throughout the state, including parts of Canterbury, Loudon, and points north. Most of their service area is rural.

Broadband access outside of cities and rich exurbs has long been an issue, but recent months of working from home and going to school online makes the value of dependable internet a lot more obvious.

“After the pandemic crisis has passed – whenever that is – there’s going to be a number of changes in workplace habits and all kinds of communication. People who don’t have (broadband) are increasingly going to be left behind,” Knox predicted.

Fair enough, but why take this to an electric cooperative rather than a phone company or a business group? Simple: “They own access to a lot of the poles.”

Knox knows this is vital because he’s on the Broadband Advisory Committee in the town of Sandwich. That group has been looking at bringing broadband to that town, which is very unusual in that it doesn’t have any cable-TV service. Cable modems are often a main high-speed internet technology in rural areas, so Sandwich is missing out.

The committee quickly found that just as important as high-tech stuff is the ability to use dead trees stuck in the ground at regular intervals.

“Broadband developers have told us … a threshold of any kind of partnership is to get reliable, easy, non-complicated access to utility poles. It can be daunting and can scare away investors,” Knox said.

The past century has created a hodge-podge of rules and regulations over who owns which poles (phone company? power company? local government?) and who gets access at what cost to which part of each one (electricity at the top and usually copper phone lines at the bottom but otherwise each yard of pole space requires negotiations).

Fights and lawsuits over pole access have slowed or thwarted many attempts to spread rural broadband via fiber-optic or coaxial cables, including at least one in New Hampshire that I know of. A change in Federal Communications Regulations on the topic produced huge debate a couple of years ago.

NHEC owns or has access to tens of thousands of poles in its service area out of half a million utility poles in the state as a whole. I tried to count them all for a story in 2016 but “at least 500,000” was the best I could do.

Petition organizers say this means it would be easier for NHEC to spread broadband in their communities than almost anybody else, while the cooperative model, in which the customers help control corporate actions through elections, makes it more likely to happen.

They also argue that the co-op’s bargaining power in combination with municipal and county governments could bring broadband developers to the table.

The petition is part of the annual vote for the board of directors. Ballots are going out to members and are due back by June 16. A two-thirds approval is required.

Whatever happens, I suspect this will not be the last time we hear about new ways to spread broadband throughout New Hampshire now that the stay-at-home regime has reminded us of its importance.

Municipal broadband, anyone?

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor

How convenient… NPR’s Planet Money just talked about this: listen/read here: https://www.npr.org/2020/05/29/865908114/small-america-vs-big-internet

Two takeaways: regulatory capture by the entrenched ISPs (cable and DSL phone providers here) is a risk; and it’s hard… experienced managers and employees are necessary to avoid financial disaster. A third takeway — it CAN work.

That Planet Money article (I love planet money) was about municipal broadband rather than cooperative-utility broadband. A similar idea but a very different legal/regulatory framework.