Drones have made it easier for Dartmouth’s Jesse Casana to do interesting archaeology, including finding things long hidden at the Shaker Village site in Enfield, but there’s a part of him which is just a little bit sorry.

“It feels like cheating a little,” admitted Casana, a professor of archaeology in the school’s department of anthropology.

Besides, he misses the kite. “I got really good at flying the kite.”

Kite? Yes, and balloons, too.

For years Casana has experimented with any technology that can get a camera up high and looking down. Hence, kites, balloons and, finally, drones.

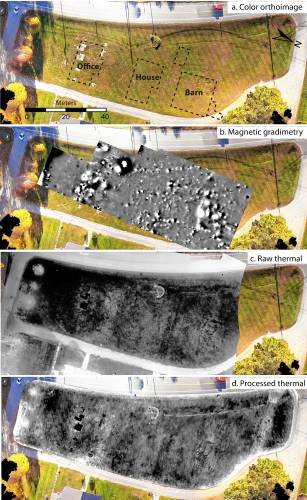

The drones that Casana and colleagues fly carry cameras that look not just at visual light but also at heat and other wavelengths, seeking information about what lurks underground.

Casana gave a simple example: “A stone wall buried below ground might be warmer or colder than the soil around it.” Measuring subtle differences in soil temperature could make that wall show up.

He has done this sort of thing for a while – his expertise is in digs in the Middle East, especially Iraq – and has accumulated enough expertise that he is the lead author of a paper with the no-nonsense title “Archaeological Aerial Thermography in Theory and Practice,” published in the latest issue of the journal Advances in Archeological Practices. It’s basically an academic how-to guide, designed to spread the word about the value of archaeologists using heat-sensing cameras (“thermography”) on drones.

“There’s a little bit of learning curve” that keeps some archaeologists at bay, Casana said. “We’ve tried to present surveys and experiments of its use, show what its limitations are, how best to deploy it.”

Peeking below-ground by looking at temperature and other non-visual wavelengths is an old idea; what’s new, he said, is improved technology.

First, the cameras.

“These are very, very high resolution. We’ve had thermal area data for decades, but it was super-expensive and then the images you collected would be very coarse spatially – resolution of 5 meters, 10 meters. You’re not going to see a little stone wall like that,” Casana said.

Second, software to process the images or overlap them to reveal new structures.

Finally, the drones.

“With ground-penetrating radar … you can maybe do a hectare (2.4 acres) a day. With the drones we can do a square kilometer a day – that’s 100 times as much,” he said.

Casana has deep New Hampshire roots – his family ran the old Weirs Beach Bowladrome – but his career took him away from the state for years until he was hired by Dartmouth. He said he has focused on the Shaker site in Enfield partly because it’s close to Dartmouth but also because there’s still much to be found, even though archaeological digs, often involving students from New Hampshire colleges, have gone on there for years.

“Most of the buildings, they don’t really know exactly where they are, where they were,” he said. “Now we can see the foundations of the buildings, along with other features like old historic pathways and roadways through the village, a couple of underground water pipes.”

He noted that thermography and other types of remote sensing can never replace the slow, mostly tedious but occasionally thrilling work of an archaeological dig. But they can guide where to dig, and provide overall context.

“You can see things that you would never be able to see with just an excavation, (because) you can’t cover that much area,” he said. “Even if you could, you would destroy the whole site, digging it all up.”

He said he plans to continue surveying the old Shaker village with different technologies, both to help our understanding of the Enfield site and to work on new techniques.

And maybe a little bit because flying drones is fun. Not as fun as a kite, but still – not bad.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor