If you have a garden of any size you’re familiar with the concept of a “microclimate,” mostly because it’s an excellent scapegoat.

The sugar snaps did lousy? Garden’s in a low spot where cold collects.

Lettuce wilted? Storm blew down a nearby tree and now it’s too sunny.

Your neighbor’s harvest is twice as good? Well of course it is, they’ve got southern exposure (or northern exposure, or something).

But there’s a more serious side to microclimate and it’s a focus of an extensive new program to help guide preservation efforts as the climate changes.

“In working for decades on this question of how do we identify land that is more resilient to climate change, we’ve gone down a bunch of different lines of evidence. The one that has really come up strong is this microclimate idea,” said Mark Anderson, director of science in the Eastern U.S. for The Nature Conservancy.

You and I, who can move around quite easily, think of “climate” in big, sweeping patterns. Concord’s climate is different from Portsmouth’s climate and Gorham’s climate but it’s the same as Bow’s or Canterbury’s, isn’t it? Not true, at least not for much of the ecosystem.

“Species experience climate very locally, especially plants,” said Anderson. “What they’re aware of is the range of microclimates right around them – that’s ‘climate’ for them.”

As an example, he noted how New England’s small population of rattlesnakes always den on south-facing hillsides, to maximize heat. If you’re setting aside property to protect rattlesnakes but only include north-facing hillsides, your effort will probably fail even if your borders are only off by a few hundred feet. Wrong microclimate.

That’s all well and good but if you’re a property owner or environmental nonprofit or conservation commission that wants to make the right choices when preserving land from development, how are you supposed to know which microclimate is which? That’s where the new data tool developed by the Nature Conservancy and Massachusetts-based Native Plant Trust comes in.

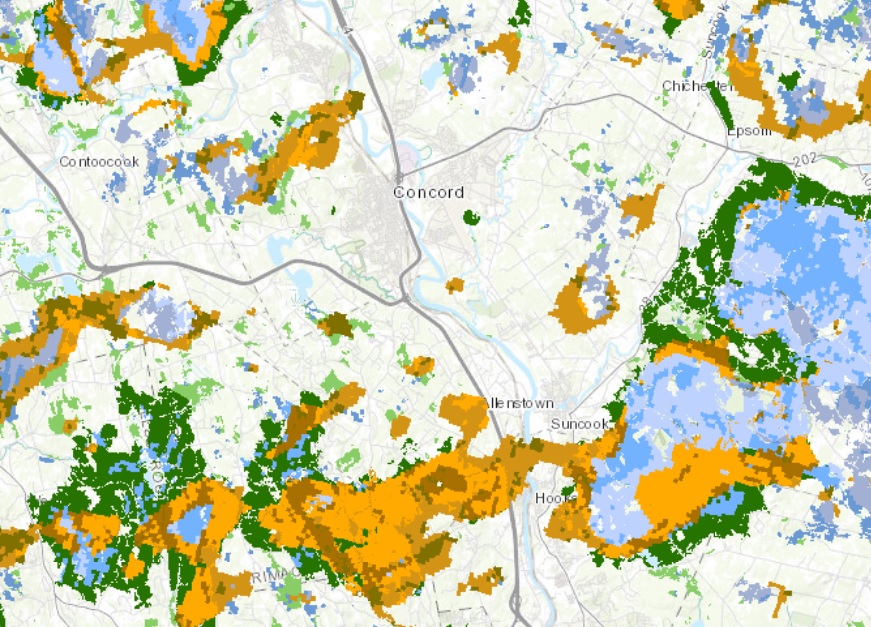

Years of on-the-ground analysis aided by the advances in GIS technology have allowed the groups to create an online map of the Northeast that analyzes the region in staggering detail. It delineates 234 Important Plant Areas (acronymed as IPAs, which could confuse microbrew fans) that have “exceptionally high rare plant diversity” and then examines whether they’re protected, secured from conversion but open to logging, threatened by development and, perhaps most interesting, “resilient to climate change” because they contain multiple connected micro-climates that create options for species.

That is important because today’s climate won’t be tomorrow’s climate – and who knows what your grandchildren’s climate will look like. One of the things we need to consider is what pieces of New Hampshire are not just the most ecologically valuable now but most likely to be valuable as the world continues to get warmer, sometimes wetter and sometimes drier, often wilder and much less predictable.

“That tool is already getting used by land trusts to find areas that are more resilient,” said Anderson. A second benefit is that it might help disparate groups use the same metrics when making hard choices. “We hope by providing this information, decisions will start to line up with each other even though we’re making them independently.”

To see the report, go to www.nativeplanttrust.org/plant-diversity-report/. The online mapping tool is at maps.tnc.org/resilientland/.

The report and online tool were rolled out last week with a high-profile online conference, after which I talked to Anderson, who has been involved in conservation for at least two decades.

“We’ve done a lot in conservation, but I think most of what we’ve done has been the low-hanging fruit – the high-elevation, northern stuff,” he said. “Now it is clear that we have to do a lot more and we have to do that new work in the low-elevation areas, rich soils, fragmented landscapes where there’s a lot of people. That will be much harder.

“On the bright side, we know what we’re doing a lot better, and there’s bipartisan support for conservation. And we have a lot better science,” he said.

What we don’t have muchanymore – not that we ever really did, although we didn’t realize it – is time. The staggering heat wave in the Pacific Northwest right now is yet another sign that 150 years of the industrial revolution has altered the entire global climate in ways so extreme that science-fiction writers in my childhood wouldn’t have dared mention because editors would pooh-pooh them.

We’ve got to stop pouring gasoline on the fire immediately through changes to the economy and our lives, although it will be expensive, difficult, unpleasant and uncomfortable, and we’ve got to prepare society for future life on a planet that’s going to be increasingly different than it has been.

In the meantime, I’m going to go water my sugar snaps. It’s embarrassing to have to keep buying them from a farm stand.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor