This post tells the story of a nasty disease that was heading toward New Hampshire but has been kept away by low-tech, sensible actions which have been adopted even though they inconvenience some people.

Any comparison to our experience with COVID is left as an exercise for the reader.

The disease in question is chronic wasting disease or CWD. It affects deer, moose and other members of the cervid family like elk and reindeer, and it is nasty. CWD is similar to mad cow disease; once symptoms start, infected animals become emaciated, drooling, disoriented and basically starve to death – wasting away, slowly and painfully.

CWD is caused by prions, a mutated form of proteins. Most of us think of “protein” only as a vaguely understood part of a healthy diet but they’re the workhorses of life. Our genes might be the blueprint for our bodies but blueprints are pointless unless something uses that information to build and operate our systems. That’s the role of proteins.

Proteins are big molecules, by molecular standards anyway, that are folded in complex ways. When they get folded slightly wrong, odd things can happen. Prions are misfolded proteins that, when they get absorbed into a living creature, can cause havoc; CWD is caused when prions infect the brain.

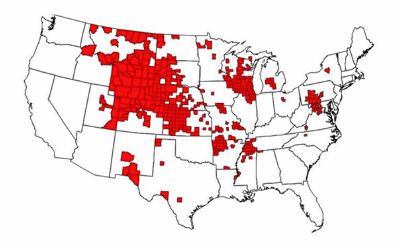

CWD was first spotted in wild deer in Colorado in 1981 and is now found throughout the Midwest and Rocky Mountains and is making its way eastward. It is spread by contact, usually eating plants near feces from a contaminated animal.

Contact with a dead deer can also spread it. which is why hunters are told to avoid the brains and spinal column of their kills. There has been no case of CWD spreading to people, even after more than 200 people ate venison from a contaminated deer at a wildlife dinner in Oneida, New York, but better safe than sorry.

I first wrote about CWD when it showed up in New York state in 2005. Everybody was expecting it to move to New England within a few years but that didn’t happen. Then in 2018, it showed up in Quebec and alarm bells rang again.

Yet the latest analysis of tissue from deer killed by hunters in the 2022 season shows that we’re still CWD-free. How’d we do it?

Biologist Becky Fuda, deer project leader for New Hampshire Fish and Game, says there is no magic bullet. There’s no vaccine, no cure, no technical or medical way to keep the prions at bay. Staying free of CWD has required planning, monitoring and cooperation.

“There’s a lot more awareness about it – most states have some sort of monitoring program,” she said. “That’s important.”

Another important move is that New Hampshire and many other states have stopped the old practice of moving deer around.

Deer, elk and other cervids are kept in game preserves around the country for hunters who want to lessen the uncertainty of finding a target. These parks, where disease can more easily spread, often sell animals to each other and if the animal is infected but not showing symptoms then, bingo!, you’ve got a new location for CWD. The outbreaks in both New York and Quebec occurred among captive cervids, which helps explain why officials were able to rush in and stop further spread.

In New Hampshire, you can’t import live cervids that are susceptible to CWD (some species are not), and you can only bring back parts of dead ones.

Hunters who return from Pennsylvania, Maine or other deer-hunting meccas can carry only “deboned meat, antlers, upper canine teeth, hides or capes with no part of the head attached, and finished taxidermy mounts. Antlers attached to skull caps or canine teeth must have all soft tissue removed,” according to state law. Further, the state discourages (although doesn’t ban) the use of hunting lures made from deer urine, which are effective but which can spread prions.

Finally there’s a continued crackdown on the feeding of wild deer, a practice that can bring animals into clusters and makes it easier to spread disease.

Fuda said research into CWD and related diseases is active and while there are some hints about possible control down the road, nothing has come of it yet.

If we want to continue to keep this nasty disease at bay, we’re going to have to continue spending taxpayer dollars on wildlife biologists to monitor and study the situation, support higher education where research to find solutions takes place and training of future biologists happens, be willing to live with legislation and regulation that isn’t popular with everybody, and restrict personal freedoms if they might inadvertently spread the disease.

None of those actions are particularly fun but that’s reality, isn’t it? Nobody said maintaining public health is easy, and that goes for deer just as it does for people.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor

I live in NH and there were 7 or 8 deer in the back of the property. One deer, looked female and possibly pregnant? She was covered in different color fur, grays and blacks and whites, but she looked like she was shedding. Her hair was tufts of fur it looked like. Almost merle. I took a few pictures, hard to see. Just a note. Not sure what it was.