Government awards given to state employees do not usually carry amusing titles. Unless you’re talking about de-icing technology in New Hampshire.

Then you’ve got awards like “Salt-n-Peppa,” “Shaken Not Stirred” and “Salt of the Earth” – given out annually by the N.H. Department of Environmental Services. They acknowledge the balancing act that road crews perform when trying to keep our cars from sliding into a ditch without turning our drinking water into brine and killing half our trees.

In Concord, that delicate act can be seen in the cabs of the city’s 17 plow trucks, each of which carry a control system that looks like a video game controller married to a stick shift designed for an octopus.

The system controls the amount of the city’s de-icing mix – pellets that combine magnesium chloride and some by products of agricultural fermentation such as beet juice – that are being tossed out by the spreader, with or without sand.

“You dial in what rate to put it. Temperature is a factor, the type of the temperature of the pavement … you base it on those differences,” said James Major, highways superintendent for the city. All those stick shifts control the system as well as all those plows.

Jim Major, highways superintendent for the city of Concord, shows the cab of a city plow truck last week. GEOFF FORESTER / Monitor staff

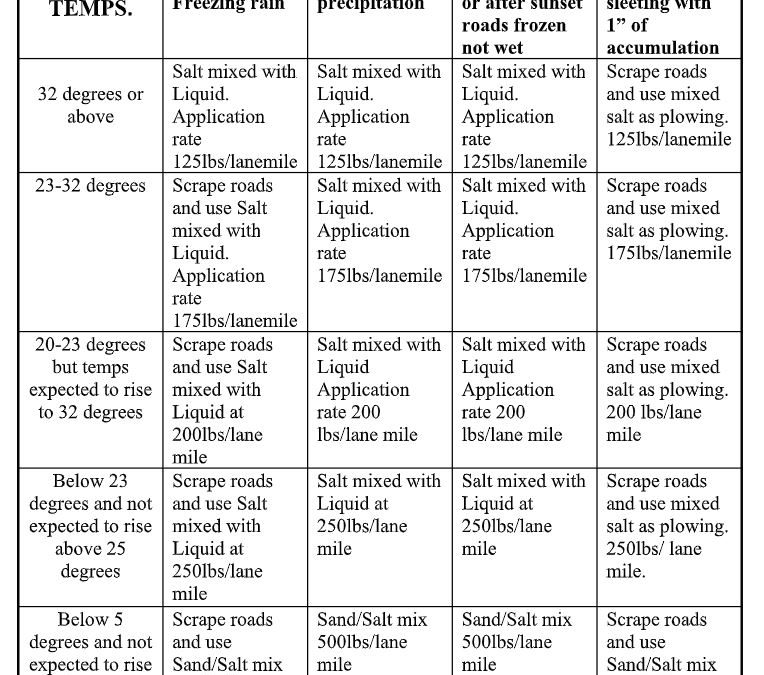

There are so many variables for the de-icing mix that drivers use a 4-by-5 decision matrix containing choices as detailed as “road temperature 20 to 23 degrees, expected to rise to 32 degrees” combined with “early morning or after sunset, roads frozen not wet.”

The resulting instruction ranges from releasing salt mixed with liquid at 125 pounds per lane mile to spreading a salt/sand mix at 500 pounds per lane mile, sometimes preceded by road scraping and sometimes not. The system is hooked into the transmission system of these hefty vehicles (60,000 pounds when fully loaded) so it knows how fast the truck is traveling and alters the spreading rate accordingly.

Why all this complexity just to melt some road ice? Because of the bugaboo of most technologies: unintended consequences.

For centuries, probably longer, we’ve known that you can melt ice and snow by dumping certain salts onto it, but the knowledge moved into the industrial scale with the arrival of automobiles and highways.

New Hampshire, incidentally, was an early enthusiast. A number of sources say that during the winter of 1941-42 we became the first state to adopt a general policy of using salt on roads. We haven’t looked back.

Salts melt ice by dissolving on contact with any liquid water and breaking into ions – charged atoms – that make it harder for water molecules to stay bonded together and form crystals. The practical effect is to lower the temperature at which water freezes so that when it is, say, 30 degrees, the ice turns back into water and your car won’t skid.

More salt can lower the freezing temperature, to an extent, and different types of salts can do it at different rates. Calcium chloride is often used by road crews because it forms three different ions and keeps water molecules from turning into crystal until the temperature falls to as low as 20 degrees below zero Fahrenheit, depending on circumstances.

The problem is that salts don’t magically disappear after the ice melts. They accumulate winter after winter, which is where the unintended consequences show up.

Salts damage plants by interfering with osmosis, the process in which water moves across membranes due to differences in salinity, and they can work theit way into our groundwater (yuck) and into rivers and ponds, harming or killing insects, fish and other aquatic species.

It’s a real problem because we use a lot of this stuff. Concord has a budget line of $450,000 to buy salt and the chloride mixture each year, which translates into well over 500 tons. Nationally, somewhere around 10 million tons is dumped onto paved surfaces each year; virtually all of that ends up in our waterways.

The Department of Environmental Services, the folks who developed the Salt-n-Peppa award, says that in 2008, New Hampshire listed 19 “chloride-impaired water bodies” under the Clean Water Act, but four years later that number had increased to 46. This is why they are pushing hard to get everybody to dump less salt on parking lots and roads or switch to less damaging (but often less effective) alternatives like acetates and brine mixtures.

Their salt reduction initiative can be found online at des.nh.gov/organization/divisions/water/wmb/was/salt-reduction-initiative/impacts.htm.

There are other unintended consequences of our road-salt habit. These free-floating ions that inhibit freezing also accelerate electrolysis, the process by which iron and oxygen bond together to form rust. That’s why all our cars fall apart, and it’s also a problem with bridges and other road infrastructure. The salt gets into the concrete and rusts out the reinforcing steel bars or mesh, known as rebar.

There’s a lot of research going on to find better alternatives, but that may be unrealistic. After all, we’re looking for a cheap, easy-to-apply system that will sharply alter the environment in ways that we want – making ice melt at unnatural temperatures – without altering it in ways we don’t want.

The best is, unfortunately, probably what we’re doing already: trying to get people to use less salt, not use it near waterways, and use alternatives when feasible.

Those of us who don’t drive 60,000-pound plow trucks can help. Unless absolutely necessary, we shouldn’t use salt-containing “ice melt” products on our sidewalks or walkways. University of New Hampshire Extension suggests a number of environmentally superior (although something messier) alternatives, like spreading gritty substances such as bird seed or sand to improve traction.

Personally, I’ve stopped trying to alter the rest of reality and alter myself instead: I put traction attachments on my outdoor boots by default. The Monitor even subsidizes them; they figured it was cheaper than having employees slip and fall in the parking lot.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor